Lawyer. Linguist. Poet. General. Inventor. He was a graduate of Union College in New York. He later graduated from Yale in 1818. He was the Brigadier General of the 3d Brigade, 1st Division of the Philadelphia Militia. His troops were raised in southern Philadelphia County. During 1844, in which most Know Nothing riots took place, Hubbell and his troops saved the Catholic churches of St. Paul and St. Joseph from destruction. He was the first to suggest the possibility of laying a telegraph cable between Newfoundland and Ireland. He also suggested the existence of a plateau at the bottom of the ocean for the cable to be laid. He partnered with Col. John Henry Sherburne in petitioning Congress in implementing the plan. In 1858, two issues of Scientific American credited Hubbell with the idea of laying the cable.

Inventor

Samuel Matthews Vauclain (1856-1940)

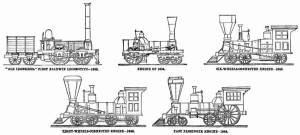

Railroad Magnate. Inventor. Philanthropist. He started working as a shop foreman at Baldwin Locomotive Works, and eventually became the company’s president and board chairman. He developed the four-cylinder compound steam engine which increased the fuel efficiency of the locomotive. During World War I, he chaired both the Locomotive and Car Committee on the Council of National Defense and the Special Advisory Committee on Plants and Munitions of the War Industries Board. During the war, Baldwin built locomotives for war effort and oversaw the Remington Rifle Company which produced munitions in Eddystone, Pennsylvania. In 1919, as president of the Baldwin Locomotive Works, he sent nearly $7 million in locomotives to postwar Poland; they were sent on credit. His board of directors considered the action a bad business deal. Baldwin, itself, could be in financial trouble, because the end of World War I, brought an end to Baldwin’s market for munitions and wartime locomotives. To the directors’ surprise, Poland repaid the debt with its last payment in August of 1929. During the course of the loan, principal and interest were paid on or before the payment date. Vauclain believed that “to be a good businessman is to be an optimist.” It was during Vauclain’s tenure as preseident that Baldwin moved its facilities from Broad and Spring Garden Streets in Philadelphia to the Eddystone plant. He was a founding member of the Kosciuszko Foundation. He was married to Ann Kearney. The S.M. Vauclain Fire Company in Ridley Township, Pennsylvania was named in recognition of Vauclain’s support and donations of equipment. In 1920 he was named an honorary member of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

Matthias William Baldwin (1795-1866)

The son of a carriage maker, was interested in mechanical things. At 16 he worked for a series of jewelers in Philadelphia. During that time he invented a process for gold plating jewelry. Later, he opened his own business. When the jewelry trade went into recession, he started a bookbinding and cloth printing business. He built a steam engine to supply power to his shops, and soon became expert at designing those engines. He married a distant cousin, Sarah C. Baldwin in 1827. They had three children. In 1830 a local museum asked Baldwin to make a working model of the “John Bull,” a locomotive, built in England, which had recently been imported to the United States. Given his knowledge of, and success with, steam engines, Baldwin was later asked to build a full size locomotive by the Philadelphia, Germantown, and Norristown Railroad. “Old Ironsides” was the result. Over time he built more locomotives. The same ingenuity which worked in the jewelry and printing businesses contributed to his success in building locomotives. One of his patents was for a high pressure steam engine; another, for a six wheel gear to stabilize locomotives as they turned curves. In 2005, he was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for his work with the steam locomotive. Baldwin also involved himself in social issues. As one of the founders of the Franklin Institute, it was his hope that young people could be encouraged to enter the “mechanical arts.” He also fought for the rights of African-Americans to vote. His activity in the abolition movement resulted in Southern states’ boycotting his locomotives. He established a school for African-American children. He also gave 10% of his money to Christian missionary work, and built a number of churches.